By Lynn Venhaus

Anyone who has experienced grief knows that moving forward, life is measured by “Before” and “After.”

“The Whale” delves into the mental and physical health problems of a morbidly obese recluse, showing us the “After” and explaining the “Before” in an emotionally honest drama by Samuel D. Hunter.

In yet another well-cast, impeccably directed production, St. Louis Actors’ Studio imbues this gut-punch of a script with empathy and authenticity.

In his play, Hunter forces us to see the complexities in human nature, so impressions aren’t so easily defined, and judgment can wait. He has crafted flawed characters who have dealt with adversity and challenges in very different ways. Yet, they are stuck in time.

First presented in 2012, Hunter later wrote a bleak screenplay adaptation for the 2022 film that won two Oscars – one for Brendan Fraser’s performance and the other for makeup.

The film, while much dimmer inside the claustrophobic apartment, is very similar to the stage play, yet the characters are more severely portrayed, and redemption doesn’t seem plausible.

Set in a small town in northern Idaho, over the course of a week, four people interact with a nearly immobile Charlie (William Roth) in his dingy living room – nurse and friend Liz (Colleen Backer), estranged daughter Ellie (Nadja Kapetanovich), ex-wife Mary (Lizi Watt), and Mormon missionary Elder Thomas (Thomas Patrick Riley).

All affected by loss and loneliness, they are each wrapped in their own cocoons, and grace has eluded them. Director Annamaria Pileggi has drawn out nuances among this exemplary cast as they reveal truths about themselves. You feel their misery, but you also see signs of hope.

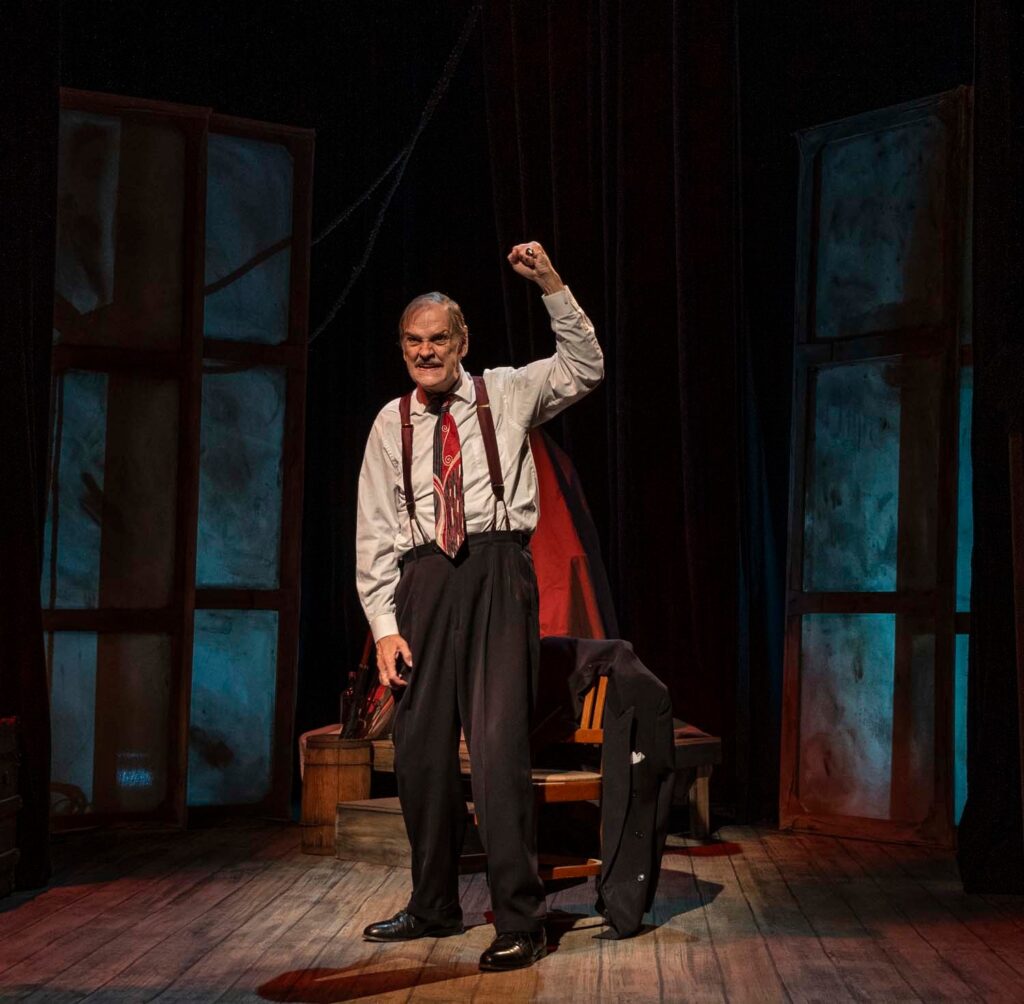

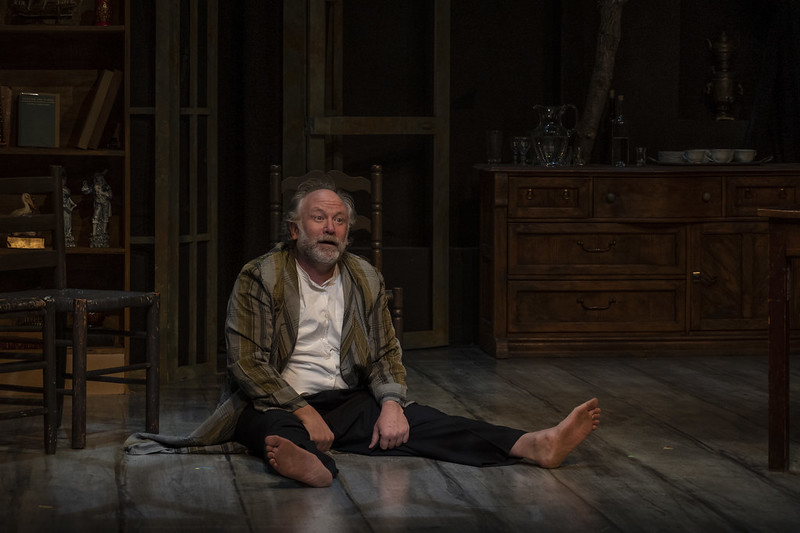

In a brave, towering performance, William Roth has never been better as Charlie, a sensitive soul whose heartache and regrets have led to self-destructive behavior. A writing instructor who now conducts classes online, he has ballooned to 600 lbs., suffers from congestive heart failure and is on a trajectory to imminent death.

Roth has delivered virtuoso performances before, notably as George in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” and as Charlie Aikin in “August: Osage County,” both at St. Louis Actors’ Studio, which he founded and is the artistic director.

But this realization is both heartfelt and haunting. Hunter enlists many ways to display Charlie’s self-loathing, visually masking his pain with an eating disorder, and describing memories from what had been an ordinary life. Roth disappears into the role, wistfully recounting happier times at the seashore with his wife and child, and then later being with his lover and former student Alan. Will he ever forgive himself for what he perceives are his failings?

Using a colloquial term, Charlie has “let himself go.” Eating his feelings since Alan’s death eight years ago, he has guilt in his psyche – but passion in his heart for literature. You feel his remorse – and his enormous capacity for love.

Through grading papers, talking to his class via computer, and reading aloud their essays, Charlie displays a fine mind, a keen grasp of literature, what authors meant, and encourages self-expression.

Conveying that love for the written word that once gave him great joy makes it much sadder that, sidelined by grief, he’s not the teacher he once was, and not entirely comfortable connecting with his students (yet, astute in his comments). The isolation, as reflected in that tiny room, is crushing.

He also has vast unconditional love for his daughter Ellie, a sullen teenager who feels abandoned and lashes out cruelly. After years of no contact, he has attempted to reconnect with her, and she is seemingly unreachable – tough, rebellious, impulsive.

Her mother, angry and filled with rage too, has kept her from establishing a relationship with her father. At 17, she hates everything and everybody, and is flunking out of school. She is repulsed by his appearance, but visits anyway — after all, he is writing her English papers, and there is a pledge of money.

Displaying hostility, confusion, forlornness, and defiance, Nadja Kapetanovich is a knockout in a finely textured performance as Ellie. It’s a sensational breakthrough performance in regional theatre.

Thomas Patrick Riley also has a breakout opportunity as Elder Thomas, and he’s splendid. He has the most complicated backstory of them all, and represents the evangelical religion that Hunter focuses on as a root to issues expressed here, particularly religious homophobia, and pointedly The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

More dots in the plot are connected through Liz, the tough-love nurse played with heartbreaking compassion by Colleen Backer, whose ability to shift moods between comic and dramatic is one of her finest features.

Liz is Alan’s sister, so there is that. And she’s trying to keep Charlie healthy and alive, but also enabling him with high-fat, high-sodium foods (fried chicken, sub sandwiches, pizza, doughnuts and soda). She offers comfort while admonishing him with lectures. It’s an endearing performance by the always entertaining Backer.

In a brief but pivotal role, Lizi Watt blows in as the blustery ex-wife Mary, whose resentment is at a full rolling boil. She’s full of outrage, and vents to Charlie on how exasperated she is about their daughter. While she’s snarling, she’s also drinking copious amounts of vodka. It’s apparent that Ellie is a mirror image of her mother.

What is interesting about these hardened characters is you see them mentally and physically soften when confronted with Charlie’s predicament – if only fleeting. There is also more humor in the play than I recall from the film, which are moments of relief from the grim subject matter and the blame game volleys.

Wearing an impressively designed body suit by Angela B. Calin and engineered and constructed by Laurie Donati of the South Coast Repertory Theatre in Costa Mesa, Calif., Roth’s physicality is key to the character, portraying the very real struggles of someone so overweight as to be in pain from the slightest exertion.

Costume Designer Teresa Doggett also worked skillfully on Roth’s prosthetics to ready him for this appearance on stage, and her casual outfit choices for the five actors were on point.

Patrick Huber’s scenic and lighting design reflects the slovenly quarters but also Charlie’s thirst for knowledge, with crammed bookshelves and papers everywhere. Props designer Emma Glose did a fine job littering the apartment with discarded food boxes, beverage containers and academia.

Caleb D. Long supervised the crafts parts as technical director. Another standout is the sound design by Kristi Gunther, also production manager, which incorporated hearing seaside noises like seagulls and the waves on the beach to evoke pleasant memories.

Others responsible for shaping this tight production: Bryn McLaughlin was the assistant director, and stage manager Amy J. Paige, with Glose her assistant.

This show’s cast was able to let us into their world, tinged with melancholy, and indicate the possibility of mercy, which is a final grace note.

And we can debate the ending for a long time, but I choose triumph, even if it is just in the teeniest glimmers of change that may be ahead for all.

St. Louis Actors’ Studio presents “The Whale” Thursday, Friday and Saturday evenings at 8 p.m. and Sundays at 3 p.m. April 5 through April 21 at The Gaslight Theatre, 358 N. Boyle. For more information: stlas.org.

Lynn (Zipfel) Venhaus has had a continuous byline in St. Louis metro region publications since 1978. She writes features and news for Belleville News-Democrat and contributes to St. Louis magazine and other publications.

She is a Rotten Tomatoes-approved film critic, currently reviews films for Webster-Kirkwood Times and KTRS Radio, covers entertainment for PopLifeSTL.com and co-hosts podcast PopLifeSTL.com…Presents.

She is a member of Critics Choice Association, where she serves on the women’s and marketing committees; Alliance of Women Film Journalists; and on the board of the St. Louis Film Critics Association. She is a founding and board member of the St. Louis Theater Circle.

She is retired from teaching journalism/media as an adjunct college instructor.